Columbia University Libraries Digital Collections: The Real Estate Record

Use your browser's Print function to print these pages.

Real estate record and builders' guide: v. 87, no. 2254: May 27, 1911

Text version:

Please note: this text may be incomplete. For more information about this OCR, view About OCR text.

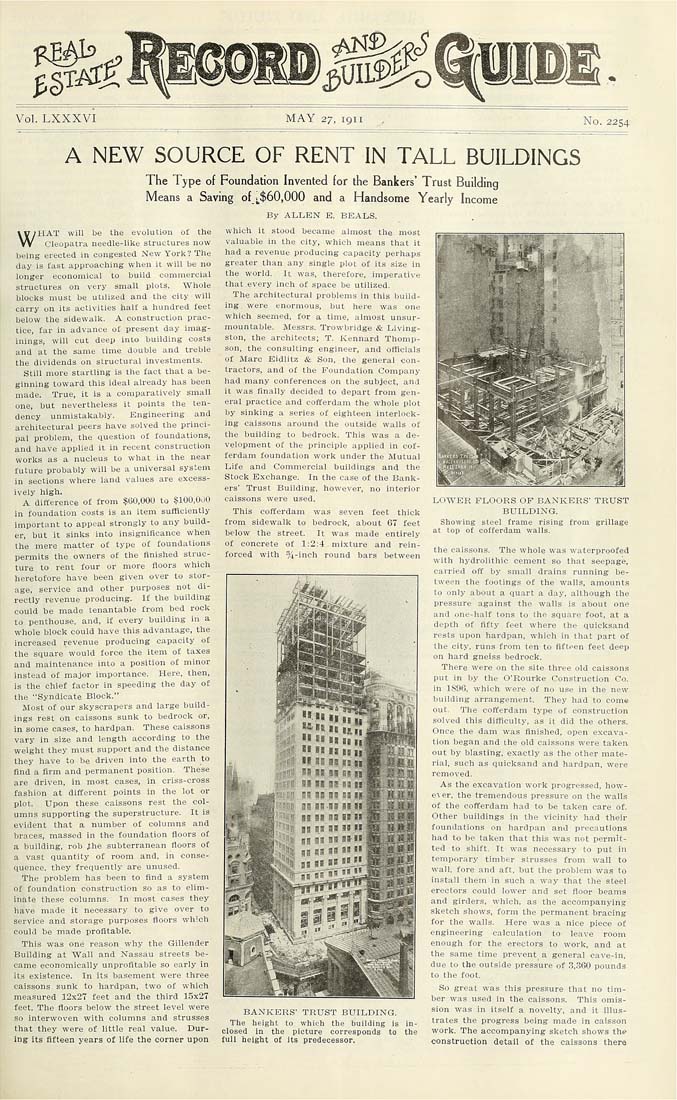

Vol. LXXXVI MAY 27, igii No. 2254 A NEW SOURCE OF RENT IN TALL BUILDINGS The Type of Foundation Invented for the Bankers' Trust Building Means a Saving of ;_$60,000 and a Handsome Yearly Income By ALLEN E. BEALS. WHAT wiil he the evolution of the Cleopatra needle-like structures now being erected m congested New York? Tlie day is tast approaching when it will L>e no longer economical to build commercial structures on very small plots. Whole blocks must be utiiiKed and the city will carry on its activities halt a liundred feet below the sidewalk. A construction prac¬ tice, far in advance of present day imag¬ inings, will cut deep into building costs and at the same time double and treble the dividends on structural investments. Stiil more startling is tlie fact that a be¬ ginning toward this ideal already has been made. True, it is a comparatively small one. but nevertheless it points the ten¬ dency unmistakably. Engineering and archilectural peers have solved the princi¬ pal problem, the question of foundations, aud have applied it in recent construction works as a nucleus to what in the near future probably will he a universal system in sections where land values are excess¬ ively high, A difference of from $00,000 to $100,000 in foundation costs is an item sufflciently important to appeal strongly to any tiuild- er, hut it sinks into insignificance when the mere matter of type of foundations permits the owners of the finished struc¬ ture to rent four or more floors which heretofore have been given over to stor¬ age, service and other purposes not di¬ rectly revenue producing. If the huilding could he made tenantable from bed rock to penthouse, and, If every building in a whole hlocli could have this advantage, the increased revenue producing capacity of the square would force the item of taxes and maintenance into a position of minor instead of major importance. Here, then, is the chief factor in speeding the day of the "Syndicate Block." Most of our skyscrapers and large huild¬ ings rest on caissons sunk to bedrock or, in some cases, to hardpan. These caissons vary in size and length according to the weight they must support and the distance they have to be driven into the earth to flnd a flrm and permanent position. These are driven, in most cases, in criss-cross fashion at different points in the lot or plot. Upon these caissons rest the col¬ umns supporting the superstructure. It is evident that a number of columns and braces, massed in the foundation floors of a building, rob fhe subterranean floors of a vast quantity of room and, in conse- quence, they frequently are unused. fhe problem has been to flnd a system of foundation construction so as to elim¬ inate these columns. In most cases they have made it necessary to give over to service and storage purposes floors which could be made profltable. This was one reason why the Gillender Building at Wall and Nassau streets be¬ came economically unprofltahle so early in its existence. In its basement were three caissons sunk to hardpan, two of which measured 12x27 feet and the third 15x:27 feet. The floors helow the street level were so interwoven with columns and strusses that they were of little real value. Dur¬ ing its fifteen years of life the corner upon which it stood became almost the most valuable in the city, which means that it had a revenue producing capacity perhaps greater than any single piot of its size in the world. It was, therefore, imperative that .every inch of space be utilised. The architectural problems in this build¬ ing were enormous, but here was one which seemed, for a time, almost unsur- mountahle. Messrs. Trowbridge & Living¬ ston, the architects; T. Kennard Thomp¬ son, the consulting engineer, and officials of Marc Eidlitz & Son, the general con¬ tractors, and of the Foundation Company had many conferences on the subject, and it was finally decided to depart from gen¬ eral practice and cofferdam the whole plot by sinking a series of eighteen interlock¬ ing caissons around the outside wails of the building lo bedrock. This was a de¬ velopment of the principle applied in cof¬ ferdam foundation work under the Mutual Life and Commercial buildings and the Stock Exchange. In the case of the Bank¬ ers' Trust Building, however, no interior caissons were used. This cofferdam was seven feet thick from sidewalk to bedrock, about 67 feet below the street. It was made entirely of concrete of 1:2:4 . mixture and rein¬ forced with !54-irich round bars between BANKERS' TRUST BUILDING. The height to which the building is in¬ closed in the picture corresponds to the full height of its predecessor. LuWEi: FLOORS OF BANKERS' TRUST BUILDING. Showing steel frame rising from grillage at top of cofferdam walls. the caissons. The whole was waterproofed with hydrolithic cement so that seepage, carried off by small drains running be¬ tween the footings of the walls, amounts to only about a quart a day. although the pressure against the walls is about one and one-half tons to the square foot, at a depth of fifty feet where the quicksand rests upon hardpan, which in that part of the city, runs from ten to fifteen feet deep on hard gneiss bedrock. There were on the site three old caissons put in by the O'Rourke Construction Co. in ISOG, which were of no use in the new building arrangement. They had to come out. The cofferdam type of construction solved this difficulty, as it did the others. Once the dam was finished, open excava¬ tion began and the old caissons were taken, out by blasting, exactly as the other mate¬ rial, such as quicksand and hardpan, were removed. As the excavation work progressed, how- ex er, the tremendous pressure on the walls of the cofferdam had to be taken care of. Other buildings in the vicinity had their foundations on hardpan and precautions had to be taken that this was not permit¬ ted to shift. It was necessary to put in temporary timber strusses from wall to wall, fore and aft. but the problem was to install them in such a way that the steel erectors could lower and set fioor beams and girders, which, as the accompanying sketch shows, form the permanent bracing- for the walls. Here was a nice piece of engineering calculation to leave room enotigh for the erectors to work, and at the same time prevent^ a general cave-in, due to the outside pressure of 3.360 pounds to the foot. So great was this pressure that no tim¬ ber was used in the caissons. This omis¬ sion was in itself a novelty, and it illus¬ trates the progress being made in caisson work. The accompanying sketch shows thp construction detail of the caissons there