Columbia University Libraries Digital Collections: The Real Estate Record

Use your browser's Print function to print these pages.

Real estate record and builders' guide: v. 61, no. 1558: January 22, 1898

Text version:

Please note: this text may be incomplete. For more information about this OCR, view About OCR text.

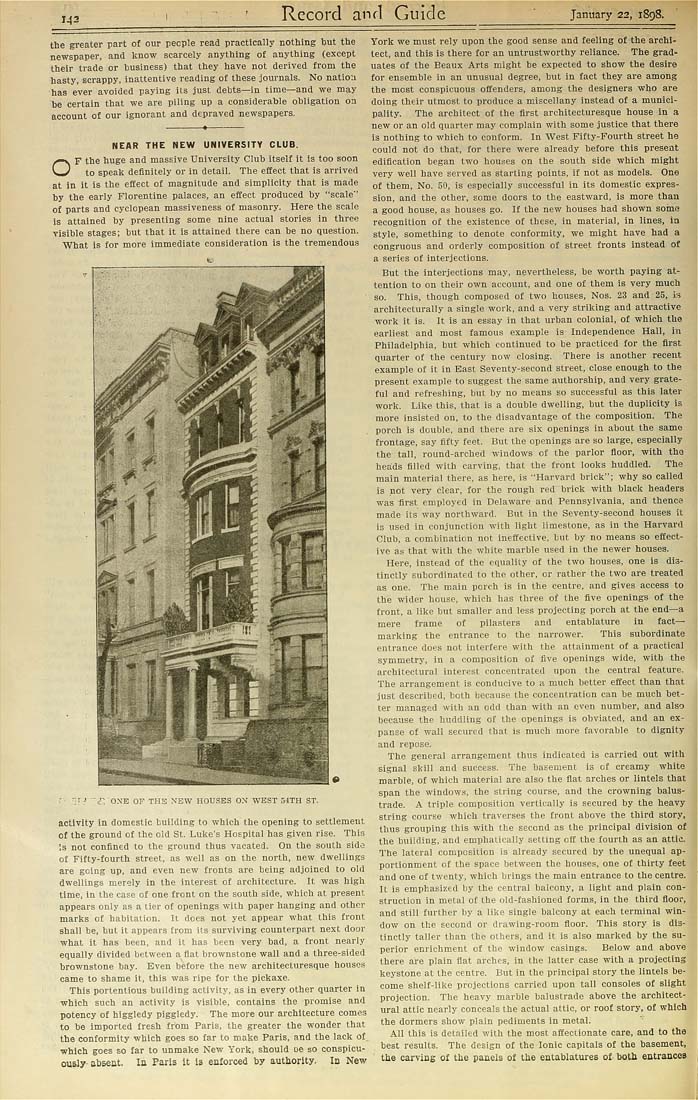

Record and Guide January 22, 189S. the greater part of our people read practically nothing but the newspaper, and know scarcely anything of anything (except their trade or business) that they have not derived from tbe hasty, scrappy, inattentive reading of these journals. No nation has ever avoided paying its just debts—in time—and we may be certain that we are piling up a considerable obligation on account of our ignorant and depraved newspapers. NEAR THE NEW UNIVERSITY CLUB. OF the huge and massive University Club itself it is too soon to speak definitely or in detail. The effect that is arrived ■ at In it is the effect of magnitude and simplicity that is made hy the early Florentine palaces, an effect produced by "scale" of parts and cyclopean massiveness of masonry. Here the scale is attained by presenting some nine actual stories in three visible stages; but that it is attained there can be no question. What is for more immediate consideration is the tremendous ,1"^ -id© ■'"■ "■"■' V. 0.\B OF THE NEW HOUSES ON WEST 3-lTH ST. activity in domestic building to which the opening to settlement of the ground of the old St. Luke's Hospital has given rise. This is not confined to the ground thus vacated. On the south side of Fifty-fourth street, as well as on the north, new dwellings are going up, and even new fronts are being adjoined to old dwellings merely in the interest of architecture. It was high time, in the case of one front on the south side, which at present appears only as a tier of openings with paper hanging and other marks of habitation. It does not yet appear what this front shall be, but it appears from its surviving counterpart next door what it has been, and it has been very had, a front nearly equally divided between a flat brownstone wall and a three-sided brownstone bay. Even before the new architecturesque houses came to shame it, this was ripe for the picliaxe. This portentious building activity, as in every other quarter in which such an activity is visible, contains the promise and potency of higgledy piggledy. The more our architecture comes to be imported fresh from Paris, the greater the wonder that the conformity which goes so far to make Paris, and the lack of which goes so far to unmake New York, should oe so conspicu¬ ously- absent, Itt Paris it Is enforced by authority. In New York we must rely upon the good sense and feeling of the archi¬ tect, and this is there for an untrustworthy reliance. The grad¬ uates of the Beaux Arts might be expected to show the desire for ensemble in an unusual degree, but in fact they are among the most conspicuous offenders, among the designers who are doing their utmost to produce a miscellany instead of a munici¬ pality. The architect of the flrst architecturesque house in a new or an old quarter may complain with some justice that there is nothing to which to conform. In West Fifty-Fourth street hs eould not do that, for there were already before this present edification began two houses on the south side which might very well have served as starting points, if not as models. 0ns of them. No. 50, is especially successful iu its domestic expres¬ sion, and the other, some doors to the eastward, is more than a good house, as houses go. If the new houses had shown some recognition of the existence of these, in material, in lines, in style, something to denote conformity, we might have had a congruous and orderly composition of street fronts instead of a series of interjections. But the interjections may, nevertheless, be worth paying at¬ tention to on their own account, and oue of tliem is very much so. Tbis, though composed of two houses, Nos. 2S and 25, i:i architecturally a single work, and a very striking and attractive work it is. It is an essay in that urban colonial, of which the earliest and most famous example is Independence Hall, in Philadelphia, but which continued to he practiced for the first quarter of the century now closing. There is another recent example of it in East Seventy-second street, close enough to the present example to suggest the same authorship, and very grate¬ ful and refreshing, but by no means so successful as this later work. Like this, that is a double dwelling, but the duplicity is more insisted on, to the disadvantage of the composition. The porch is double, and there are six openings in about the same frontage, say fifty feet. But the openings are so large, especially the- tall, round-arched windows of tbe parlor fioor, with tho heads filled with carving, that the front looks huddled. The main material there, as here, is "Harvard brick"; why so called is not very clear, for the rough red brick with black headers was first employed in Delaware and Pennsylvania, and thence made its way northward. But in the Seventy-second houses it is used in conjunction with light limestone, as in the Harvard Club, a combination not ineffective, but by no means so effect¬ ive as that with the white marble used in the newer houses. Here, instead of the equality of the two houses, one is dis¬ tinctly subordinated to the other, or rather the two are treated as one. The main porch is in the centre, and gives access to the wider house, which has three of the five openings of the front, a like but smaller and less projecting porch at the end—a mere frame of pilasters and entablature in fact- marking the entrance to the narrower. This subordinate entrance does not interfere with the attainment of a practical symmetry, in a composition of flve openings wide, with the architectural interest concentrated upon the central feature. The arrangement is conducive to a much better effect than that just described, both because the concentration can be much bet¬ ter managed with an odd than with an even number, and also because the huddling of the openings is obviated, and an ex¬ panse of wall secured that is much more favorable to dignity and repose. The general arrangement thus indicated is carried out with signal skill and success. The basement is of creamy white marble, of which material are also the flat arches or lintels that span the windows, the string course, and the crowning balus¬ trade. A triple composition vertically is secured by the heavy string course which traverses the front above the third story, thus grouping this with the second as the principal division of the building, and emphatically setting off the fourth as an attic. The lateral composition is already secured by the unequal ap¬ portionment of the space between the houses, one of thirty feet and one of twenty, which brings the main entrance to the centre. It is emphasized by the central balcony, a light and plain con¬ struction in metal of the old-fashioned forms, in the third floor, and still further by a like single balcony at each terminal win¬ dow on the second or drawing-room floor. This story is dis¬ tinctly taller than the others, and it is also marked by the su¬ perior enrichment of the window casings. Below and above there are plain flat arches, in the latter case with a projecting keystone at the centre. But in the principal story the lintels be¬ come shelf-like projections carried upon tali consoles of slight projection. The heavy marble balustrade above the architect¬ ural attic nearly conceals the actual attic, or roof story, of which the dormers show plain pediments in metal. All this is detailed with the most affectionate care, and to tho best results. The design of the Ionic capitals of the basement, the carving of the panels of the entablatures of both entranceft