Please note: this text may be incomplete. For more information about this OCR, view

About OCR text.

Record and Guide

January 22, 189S.

the greater part of our people read practically nothing but the

newspaper, and know scarcely anything of anything (except

their trade or business) that they have not derived from tbe

hasty, scrappy, inattentive reading of these journals. No nation

has ever avoided paying its just debts—in time—and we may

be certain that we are piling up a considerable obligation on

account of our ignorant and depraved newspapers.

NEAR THE NEW UNIVERSITY CLUB.

OF the huge and massive University Club itself it is too soon

to speak definitely or in detail. The effect that is arrived

■ at In it is the effect of magnitude and simplicity that is made

hy the early Florentine palaces, an effect produced by "scale"

of parts and cyclopean massiveness of masonry. Here the scale

is attained by presenting some nine actual stories in three

visible stages; but that it is attained there can be no question.

What is for more immediate consideration is the tremendous

,1"^

-id©

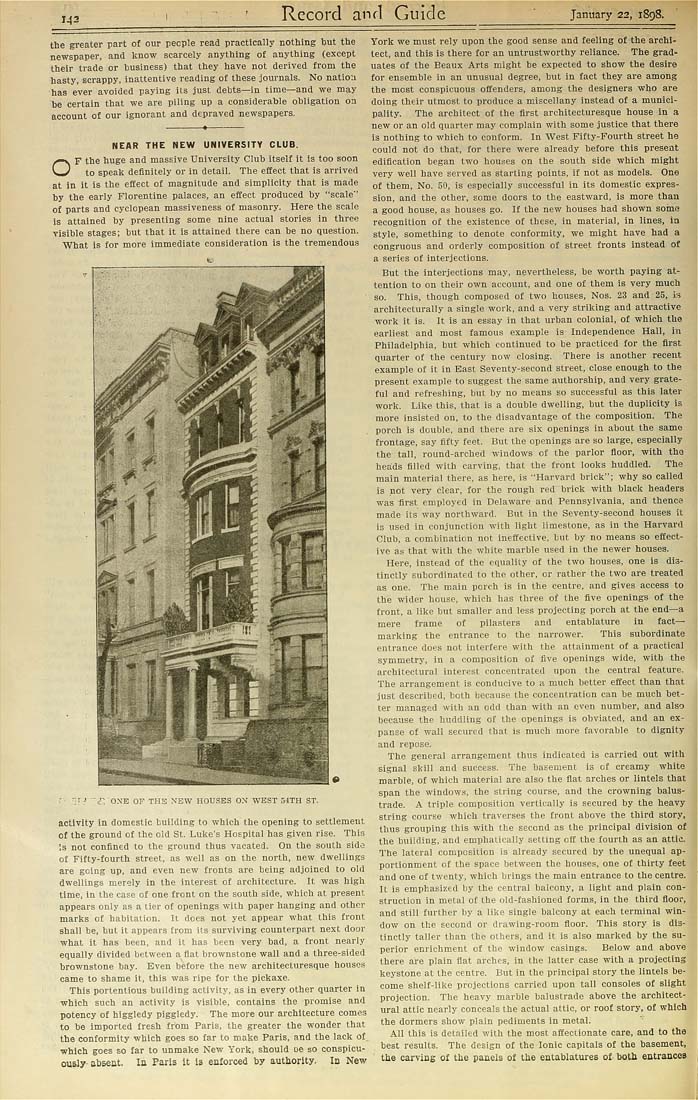

■'"■ "■"■' V. 0.\B OF THE NEW HOUSES ON WEST 3-lTH ST.

activity in domestic building to which the opening to settlement

of the ground of the old St. Luke's Hospital has given rise. This

is not confined to the ground thus vacated. On the south side

of Fifty-fourth street, as well as on the north, new dwellings

are going up, and even new fronts are being adjoined to old

dwellings merely in the interest of architecture. It was high

time, in the case of one front on the south side, which at present

appears only as a tier of openings with paper hanging and other

marks of habitation. It does not yet appear what this front

shall be, but it appears from its surviving counterpart next door

what it has been, and it has been very had, a front nearly

equally divided between a flat brownstone wall and a three-sided

brownstone bay. Even before the new architecturesque houses

came to shame it, this was ripe for the picliaxe.

This portentious building activity, as in every other quarter in

which such an activity is visible, contains the promise and

potency of higgledy piggledy. The more our architecture comes

to be imported fresh from Paris, the greater the wonder that

the conformity which goes so far to make Paris, and the lack of

which goes so far to unmake New York, should oe so conspicu¬

ously- absent, Itt Paris it Is enforced by authority. In New

York we must rely upon the good sense and feeling of the archi¬

tect, and this is there for an untrustworthy reliance. The grad¬

uates of the Beaux Arts might be expected to show the desire

for ensemble in an unusual degree, but in fact they are among

the most conspicuous offenders, among the designers who are

doing their utmost to produce a miscellany instead of a munici¬

pality. The architect of the flrst architecturesque house in a

new or an old quarter may complain with some justice that there

is nothing to which to conform. In West Fifty-Fourth street hs

eould not do that, for there were already before this present

edification began two houses on the south side which might

very well have served as starting points, if not as models. 0ns

of them. No. 50, is especially successful iu its domestic expres¬

sion, and the other, some doors to the eastward, is more than

a good house, as houses go. If the new houses had shown some

recognition of the existence of these, in material, in lines, in

style, something to denote conformity, we might have had a

congruous and orderly composition of street fronts instead of

a series of interjections.

But the interjections may, nevertheless, be worth paying at¬

tention to on their own account, and oue of tliem is very much

so. Tbis, though composed of two houses, Nos. 2S and 25, i:i

architecturally a single work, and a very striking and attractive

work it is. It is an essay in that urban colonial, of which the

earliest and most famous example is Independence Hall, in

Philadelphia, but which continued to he practiced for the first

quarter of the century now closing. There is another recent

example of it in East Seventy-second street, close enough to the

present example to suggest the same authorship, and very grate¬

ful and refreshing, but by no means so successful as this later

work. Like this, that is a double dwelling, but the duplicity is

more insisted on, to the disadvantage of the composition. The

porch is double, and there are six openings in about the same

frontage, say fifty feet. But the openings are so large, especially

the- tall, round-arched windows of tbe parlor fioor, with tho

heads filled with carving, that the front looks huddled. The

main material there, as here, is "Harvard brick"; why so called

is not very clear, for the rough red brick with black headers

was first employed in Delaware and Pennsylvania, and thence

made its way northward. But in the Seventy-second houses it

is used in conjunction with light limestone, as in the Harvard

Club, a combination not ineffective, but by no means so effect¬

ive as that with the white marble used in the newer houses.

Here, instead of the equality of the two houses, one is dis¬

tinctly subordinated to the other, or rather the two are treated

as one. The main porch is in the centre, and gives access to

the wider house, which has three of the five openings of the

front, a like but smaller and less projecting porch at the end—a

mere frame of pilasters and entablature in fact-

marking the entrance to the narrower. This subordinate

entrance does not interfere with the attainment of a practical

symmetry, in a composition of flve openings wide, with the

architectural interest concentrated upon the central feature.

The arrangement is conducive to a much better effect than that

just described, both because the concentration can be much bet¬

ter managed with an odd than with an even number, and also

because the huddling of the openings is obviated, and an ex¬

panse of wall secured that is much more favorable to dignity

and repose.

The general arrangement thus indicated is carried out with

signal skill and success. The basement is of creamy white

marble, of which material are also the flat arches or lintels that

span the windows, the string course, and the crowning balus¬

trade. A triple composition vertically is secured by the heavy

string course which traverses the front above the third story,

thus grouping this with the second as the principal division of

the building, and emphatically setting off the fourth as an attic.

The lateral composition is already secured by the unequal ap¬

portionment of the space between the houses, one of thirty feet

and one of twenty, which brings the main entrance to the centre.

It is emphasized by the central balcony, a light and plain con¬

struction in metal of the old-fashioned forms, in the third floor,

and still further by a like single balcony at each terminal win¬

dow on the second or drawing-room floor. This story is dis¬

tinctly taller than the others, and it is also marked by the su¬

perior enrichment of the window casings. Below and above

there are plain flat arches, in the latter case with a projecting

keystone at the centre. But in the principal story the lintels be¬

come shelf-like projections carried upon tali consoles of slight

projection. The heavy marble balustrade above the architect¬

ural attic nearly conceals the actual attic, or roof story, of which

the dormers show plain pediments in metal.

All this is detailed with the most affectionate care, and to tho

best results. The design of the Ionic capitals of the basement,

the carving of the panels of the entablatures of both entranceft